2018 Systems Thinking Course

Course Description

Complex systems are at the root of our world’s most pressing problems and largest opportunities. This course focuses on concepts and practices used to define and analyze systems, providing opportunities for students to build competencies with systems thinking to describe, assess, understand and manage complexity from local to global scales. This course considers a range of topics including systems science, complexity, behavior of complex adaptive systems, networks, emergence and patterns of organization. Participants will gain direct experience applying a systems lens as both students and teachers by preparing and presenting a course project on one topic of their choice and working together to develop a syllabus for a large introductory course pilot on systems thinking.

Syllabus

Agronomy 375 001 Fall 2018 Jahn

Course Evaluations

Course Journal Guidelines

Systems_Thinking-Reflective_Journal_Assignment-V2

Course Schedule

Week 1

Session 1-Introduction to Systems Through an Introduction to Each Other

Description:

- Introduction and Course History – Molly

- Recap of the history of the class as a capstone, development into its current state.

- Cathy’s Question Activity – Rob (with Molly)

- Begin by having students form tables into groups rather than rows. Students were asked to individually come up with two multiple choice questions that they would like to ask their peers to get to know them. Then, in groups, 2 questions per group are chosen or developed and written on the white boards in the room. Students mark their answer for every question (takes a few minutes) then they return to their seats.

- We discuss:

- Trends in the questions, biases in the questions, differences in the questions. What was there? What was missing? How does where we’re from change what we ask?

- After discussion we have the groups write a new question: Either a “better” question that they could learn more from, or a “taboo” question—something that is normally not acceptable to ask. These questions aren’t answered by the class, but contribute to the discussion of what factors shape the questions we ask, and how are those factors visible.

- This activity gets at a core lesson of the course, which is:

- The questions you ask determine what you can learn.

- We then spent a brief amount of time going through the syllabus, describing the course texts, and, specifically, highlighting the class attendance and timeliness rules, which will be emphasized throughout the semester.

- We also did an “awkward icebreaker,” to get to know names, majors and favorite ice cream flavors.

- Notes from class:

- The group engaged quickly and seemed ready to contribute. The non-traditional first class probably helped with this. It seems they don’t know exactly what to expect going forward, but I suspect they are interested and simply glad to have an obviously non-traditional class in their schedules.

Materials:

- Activity: Question Activity

- Videos: Systems Thinking-A Little Film About a Big Idea

Week 2

Session 2-Thinking in Systems

Description:

- Rob lectures on systems, referencing Meadows and the video by way of the John Muir quote:

- “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe”

- Rob unpacked this quote, asking students: How do we decide what can be picked out? What is “the universe” in any given system? How are the parts hitched together? Are certain parts better than others?

- Also asked, “who was john muir?”

- This lead us to a discussion of national parks, the quote was applied to systems thinking in the national park’s context. What are the connections? are there hierarchies? When we divide the land into parks what are we doing? How do the national parks affect us, the world?

- Molly points out the way students respond to these questions: Some with questions, some by removing an element of the systems and considering the hypothetical effects.

- Molly: “acknowledging that there are many unknown unknowns is important. It’s a posture of humility toward the system. indigenous cultures do that especially well.”

- Rob: “the materials of a spider’s web vary across its parts. Can we ask which is the most important, and which has which purpose?”

- Student: Salience varies across systems. Systems are stacked on top of one another, so something that matters in one system may matter differently in another.

- Rob spent some time on Meadows, regarding the bathtub as a system, acknowledging stocks and flows, and discussing various ways that feedback loops could affect the system.

- Activity:

- Systems, and systems researchers. Researchers need to answer the questions: What are the parts of this system? What are the relationships?

- Rule of the game (unbeknownst to the researchers): every participating person freely selects 2 people around them. When the game begins, each individual must make themselves equidistant from the 2 people they selected.

- In a large group of ~20 students, this game looked like chaos. Everyone was moving about and constantly changing as they attempted to get into position. As one person changed in relation to their triad, other triads that depended on them also had to move.

- When the researchers came in to figure out what was going on they were baffled, and it wasn’t until they broke into smaller groups that each researcher found a lead. By the end all researchers had established some true aspects of the game, but no single researcher had really pieced it all together.

- One student asked if every version of this system was solvable, meaning that participants had found a stasis that met the goals of each triad.

- The discussion and excitement around this game was bountiful.

Materials:

- Activity: Systems Interactions

- Readings:

- Meadows, Donella H. Thinking in Systems. (2008) Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, VT. Introduction & Chapter 1

Session 3-History of Thought (Paradigms)

Description:

- Molly lectures on systems and paradigms:

- Recall and review the previous lectures, their purposes and their lessons

- The answers we get lie in the questions we ask

- Becoming “systems scientists”

- What is a system?

- Parts/units

- Rules by which systems move

- Description of the system (boxes and arrows)

- Intervened in the system

- Intervention as a way to query the system,

- To get it to reveal its truths

- (note the difference between description and intervention)

- Aside: Irony that systems ecology was discovered in the ‘50s when the development of the bomb led to pervasive spread of nuclear elements throughout the surrounding ecosystems. They then understood that materials move through systems. Molly notes that “describing a system is not an intervention.” Ecology gets this confused a lot – describing it doesn’t change the system, it helps us see it more clearly, but it doesn’t change it. (ecology, social justice, etc.)

- Intervention as a means of querying the system. (oak ridge on accident, our researchers doing intentional experiments in Tuesday’s class)

- When seeing a system with elements and dynamics we literally may be seeing things that were not seen before

- Rob notes that we are not always able to intervene in a system – for example we can’t just make 2 galaxies collide and see what happens. We have to observe carefully, learn about the stagnant elements, and suppose/observe what happens during a shift. Further, we can’t see constants. We only note perturbations and changes. Fish don’t know they’re in water, we don’t know we’re in X. “You can’t tell what’s going on unless there are dynamics, unless something changes.

- With a systems view: we can organize “cases” into “affected” or not.

- Molly: Capra and luisi is the only textbook on systems thinking. But this paradigm is “crashing” over many, many disciplines.

- Molly: We use narratives as a tool in systems thinking. Humans are hyper-tuned to pick up on narratives.

- Narratives can be very rigorous, and are incredibly powerful tools

- Capra highlights of humanity up through 1500s.

- In small stable communities, nature played a very prominent and decisive role. Spirituality toward nature was really important.

- “Organic” communities

- Condition of knowledge, who controlled it: The church.

- If you disagreed with the church, you could be killed. Further, there was no clear alternative and they had institutional control of lots of resources and mass cultural power.

- The church + Aristotle shaped western thinking. Thomas Aquinas pulled the two of these things together in the 15 and 1600s. Prior to Aquinas there was a single static body of knowledge (recognized by the mainstream).

- John Wycliffe 1300s, went to Oxford. Oxford has a system of colleges that are built like forts (jesus college) because scholars were vulnerable. Wycliffe studied Latin, and read the bible. Then he began to translate the bible into common English. This subverts the churches “shock and awe” branding of cathedrals and latin sermons, and the common people were then able to hold the church up to a power that was holier than it. Wycliffe started the group known as “the lollards.” Nothing about hierarchy, or tithes or penance. This was so dangerous to the church that they ordered all the English bibles burned and all the lollards killed in 1382 (for treason to the church, or heresy or whatever). They burned his body in 1412 to prevent his body and soul from reconvening in heaven. The Lollards wrote him a beautiful poem, of his dust spreading all around the world. People hid the bibles and hid the lollards to save the English bible.

- Friedrich Wilhelm – Emperor of Prussia, protestant, late 1700s. He founded the idea of pietism: the way to get to heaven is to do good works on earth for your fellow man and woman. He felt that scholars had a special obligation to go out and do good. He revolutionized German academia and German education by making everyone go to his school of pietism. He wanted everyone in the empire to be literate. This university is in the german research university tradition.

- Paradigm is a way of thinking, a way of seeing. With huge implications to what we do.

- Molly genetically engineers a tomato to become resistant to a tomato plague in Africa.

- Molly didn’t know that USAID was really just meant to give money to universities, not to do anything of importance. She didn’t know this and did some “telephone breeding” to get trials started in Mali and bring back tomatoes. Crashed the market and the cannery didn’t work. Uh-oh.

- Paradigm: More, more, more is better, better, better.

- Being more efficient in the use of a resource doesn’t necessarily save you from going off the cliff (Sustainability is about not going over thresholds).

- Tomato story as a Kuhnian anomaly. (divergence from normal science. Too many tomatoes didn’t make people better). Crashed the food system by having success in one lane.

- “Food security” as a marketing move, “a label” from USAID in the early ‘90s

- Further elaborates on Kuhn and his references to paradigms in normal science – based on Molly’s summary and excerpts from the book.

- Books referenced in Molly’s Lecture:

- Bragg, Melvyn. The Adventure of English: The Biography of a Language. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2003.

- Hochschild, Adam. Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2005.

- Kuhn, Thomas. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 2nd ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Materials:

- Supporting Documents

- Readings:

- Capra, Fritjof and Pier Luigi Luisi, The Systems View of Life. (2014). Cambridge University Press (Introduction, Ch. 1, 2)

- Reflective Journal

- Prompt:

- Pick a system that you are a part of and describe the parts, relationships, and functions of the system using language from this weeks’ readings, video, and classes. Do you think this is really a system? Why or why not? Note: You can’t use family or classes as the system you describe.

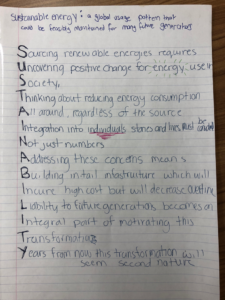

- Student Submission Examples:

- Student A

- Student B

- Student C

- Student D

- Student E

- Prompt:

Week 3

Session 4-Systems Basics I (Definitions, Concepts)

Description:

- Recap of Molly’s lecture:

- questions about paradigms, the paradigm change of continental drift.

- The static system of seeing continents couldn’t explain why they seemed to fit together. Why did we prefer the vision of a static earth? We assume that it isn’t changing, but in actuality it always is.

- Briefly talk on Molly’s lecture: Shocks to system, the power of individuals to change systems, the concept of thresholds in systems (non-linear cause and effect).

- Meadows Chp 2

- 1 stock systems – Bathtub, populations, room temperature, oatmeal in cupboard.

- 2 stock systems – predators/prey, agricultural capital/harvest

- Feedback loop

- Reinforcing loop – goes faster the more it happens

- An amp and microphone, returns on a bank account, birthrates

- Balancing loop – goes slower the more it happens

- Rabbits and resources, the more they consume the less they can be supported.

- The death rate generally does this.

- Stocks vs. flows: Stocks can be depleted by outflows and inflows.

- As opposed to information which cannot be depleted in that way

- Delays and time dependence in systems loops

- Time changes how we see it.

- The information coming from the feedback loop doesn’t change the current stock, it can only effect the future stock.

- Page 51 – the car lot example of stock and expected sales.

- Calculus is an excellent tool for considering rates of change

- Limitations: Conservation of matter, conservation of energy, and stocks can be depleted or increased by inputs and outputs.

- When we look for relationships: Imposing a point of view on a system to try and establish relationships.

- 12345 vs. 54132. Numerical and alphabetical. The relationships here are not inherent to the parts of the system, they are imposed by evaluation.

- The system boundaries are choices.

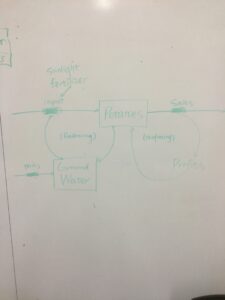

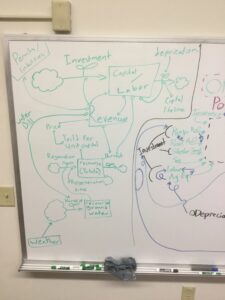

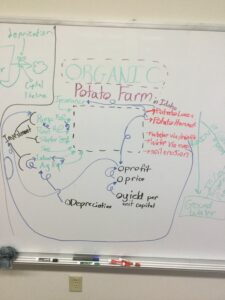

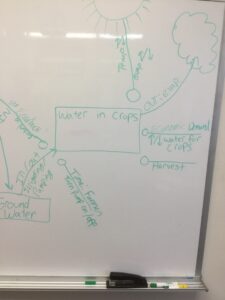

- Group Activity (teams of 5): Using terms from class and the reading, make a systems diagram of a potato farm that uses groundwater.

- We then had the students draw out the system their team came up with on the board. We discussed how each group’s differed and how they determined where the boundaries of the system should fall.

Materials:

- Readings:

- Meadows, Donella H. Thinking in Systems. (2008) Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, VT. Chapter 2

Session 5-Systems Basics II (Connections in Systems)

Description:

- Molly and Rob both spent a few minutes reflecting on the journals and the role/importance of “interventions” in class.

- We then went back to consider the potato system that were created in the previous class. Each group sat up in front, like an expert panel, and the class asked them questions about their model. Why did they include what they did? What did they focus on? How were feedbacks determined? What is this system a model of?

- All four teams went, and presented a variety of models: Some more complex and some more feedback oriented, with varying numbers of nodes/connections etc.

- Interesting notes/questions from this activity:

- Molly: Virtually infinite ways to think about any system. So, it’s about the assumptions we make. In systems thinking, as opposed to reductionist science, we are very clear about what these assumptions are.

- Systems always have a temporal feature.

- Symbols for mapping systems are different across disciplines.

- Rob: Every model is partial

- This exercise took us through the rest of the class, and encouraged a lot of good contribution and conversation between the students.

Materials:

- Readings:

- Capra, Fritjof and Pier Luigi Luisi, The Systems View of Life. (2014). Cambridge University Press (Ch. 4, 5)

- Videos:

- An Ecology of Mind-A Daughter’s portrait of Gregory Bateson

- Supporting Doc:

- Reflective Journal

- Prompt

- When Molly helped introduce a new variety of tomato to farmers in Mali, it was in response to a “problem” that she and her colleagues had been called upon to help resolve. “Success” seemed straight forward, but, as we now know, things weren’t quite that simple. Try to apply some systems thinking terms and discuss Molly’s story in your own words. In particular think about stocks, flows, feedbacks, time delays, and system boundaries. Does changing the boundary of the “system” you’re working with change the definition of the “problem?” Might it also change the definition of “success” and “failure?” Does changing your view of the system actually create a new problem to solve?

- Student Submission Examples:

- Student A

- Student B

- Student C

- Student D

- Student E

- Prompt

Week 4

Session 6-Systems Behavior I

Description:

- A few slides from Rob: Reminders about familiar systems

- How we can map the connections, determine the boundaries, known knowns, known unknowns, unknown unknowns.

- Recap of our potato models:

- What in the models can’t be measured or researched?

- Are potatoes more “random” than people?

- We can observe the past, but that does not always allow us to predict the future.

- The Agro-IBIS model

- What is missing from this model?

- What did we capture in our models that wasn’t in this model?

- (economic factors, ground water)

- Group Activity

- What are the connections you made between the Meadows chapters and An Ecology of Mind?

- What are questions that you have after the readings and the film?

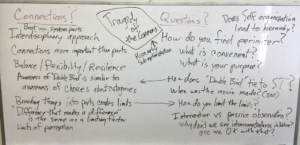

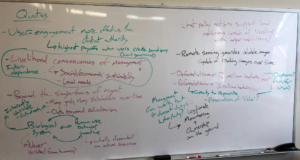

- (see photo of whiteboard from discussion)

- Groups documented and shared their thoughts. Included questions and connections about:

- Resilience and limits, about passive observation versus intervention into systems.

- Lots of talk about the double bind and how it relates to systems thinking and systems analysis. How can we escape double binds? (Timing, outside solutions, solidarity were all options discussed).

- What might Bateson have said about how we determine the perimeter of a system? (What we see in the world is a set of choices we made in our mind).

- One group thought that Meadows talk of limits was similar to Bateson’s concept of “the difference that makes a difference.”

- Why don’t we always see the interconnectedness in nature? Changes in our goals, our ability to perceive, our institutional imperatives, our time-scale, our technology.

- The tragedy of the commons – When the goals of the sub-system dominate the behavior of the whole.

- Hierarchy and self-organization. Does self-organization necessitate hierarchy?

- How do we get better at seeing the world non-linearly?

- How do we integrate Bateson’s philosophy into more practical situations and problems?

Materials:

- Readings:

- Meadows, Donella H. Thinking in Systems. (2008) Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, VT. Chapter 3 & 4

Session 7-System Behavior II (Thresholds, Tipping Points)

Description:

- Began by filling in Molly on the previous class, with this photo on the board to support:

- Molly asked, “How do we choose boundaries in systems?”

- Students responded:

- Physical relationships (often visual)

- The goal of the system

- Ease of Communication

- The purpose of the model – to educate or to reveal?

- The values of the audience and creator

- Subconscious structures (historical, cultural) – anecdote about family relationship nouns in Indonesia.

- The context for the system

- Material inflow/outflows

- Our recap discussion also covered:

- The double bind and implications for race in America and gender in binaries. We recognized that when enough people become aware that they’re in a double bind, they may be able to change the conditions that created it. The way we choose to set limits creates the double bind.

- When one is in the double bind but not recognizing it, they direct their frustration inward, as there is no other known place to direct it. However, when we recognize the limits creating the double bind situation we may be more capable of resolving it.

- Rob talked about boundaries in disciplinary science: The fossil fuel crises creates a situation where different perspectives become mutually exclusive. It is not until the experts recognize the situation that their perspectives have created that they can work together to resolve.

- The Baha’I faith changes conceptions of family to view all of humanity as literally one body.

- Nora Bateson Quotes (Small Arcs of Large Circles, Tears at the Bus Stop, page 67):

- “I see that the coming generations will be faced with a translation task. They will carry two narratives simultaneously that are seemingly at odds. One is the story of a world that is broken and binary. The other is the wider focus of a world of stories, woven and tangled in ever-changing response to one another. Somehow these coming generations will tightrope through the transactions that fill their days.”

- “The violence of breaking the world into bits and never putting it back together again substantiates the kind of blindness in which we have separated ecology from economy, and psychology from politics.”

- Healthy Grown Potatoes Anecdote

- The WI Central Sands are excellent for growing potatoes. They have loamy soil, and generally good conditions for the crop. However, due to the sand in the soil, pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers seep through to the groundwater and run into the watershed, causing contamination of ecosystems and water, even contaminating underground aquifers.

- Potato farmers, stereotypically, don’t care about these ecological consequences, unless they like to hunt or fish trout, perhaps.

- Eventually, these practices began to harm the crane populations in the region. The harm of this signature species enlivened conservationists and lead to an escalating debate with potato farmers. These conflicts are a hallmark of the linear view: Progress grows unabated for a period of time, until, eventually, different goals and strategies begin to “run into” each other. In this case, the potato farmers ran into the folks who wanted to save the cranes.

- These naturalists were inspired by Aldo Leopold, an icon of the state and region, who advocated for conservation and integrated land ethics. The debate went on with some animosity for a time, and eventually the UW Extension, under the purview of the Wisconsin idea, intervened. The WWF was also involved. This third party captured the trust of both groups, and was able to broker a new solution through integrated crop management. Healthy Grown Potatoes was the name of the initiative which enabled increased potato quality, sufficient yield and didn’t harm the ecosystem. It was, in fact, better for the environment than USDA organic standards, due to the disuse of copper fertilizers.

- The farmers were proud of their commitments and new growing style, and conservationists were glad for the ecosystems. However, an issue arose when large distributors, like Walmart, made it clear that they were not willing to charge customers a price premium for the higher quality, more sustainable potatoes. As a result, Healthy Grown farmers had to sell at the market rate, which cut into their profit margins.

- A number of years past, and despite the loss of profits, the Healthy Grown farmers remained committed to the new strategy. As it turns out, they were continuing for moral reasons, not the customary economic ones. The farmers felt they had a moral obligation to the land, and, now that they realized the harm of their old ways, they didn’t want to return to that technique. This would beguile most economic theorists, but nonetheless it was the case.

- As more time passed and economic studies by the UW were conducted, a realization was made: despite the lower profit margins, the farmers’ fortitude in their new practice had, over time, increased the market share of Healthy Grown potatoes. So, while the solution wasn’t at first economically viable due to profit margins, the farmers’ appreciation for the new strategy enabled them to continue Healthy Grown production long enough for customers to buy more of these superior potatoes. The increased market share generated the revenues the farmers’ needed to maintain their livelihoods and the ecosystems at once.

- The class ended with some brief questions about the story, including comments about the importance of the shift in values of consumers, producers, and retailers like Walmart.

- Molly ended us by reminding us of important questions to ask in systems thinking?

- Who am I in relation to this system?

- What are the unknown unknowns in the situation?

- How is the system bounded?

Materials:

- Readings:

- Capra, Fritjof and Pier Luigi Luisi,The Systems View of Life. (2014). Cambridge University Press (Ch. 6).

- In-Class Reading: Healthy Grown Potatoes Reading

- https://wisconsinpotatoes.com/admin/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Lets-Expand-Healthy-Grown-feat.pdf

- Related Videos:

- Wisconsin Healthy Grown Potato Program, part 1/3, Overview and Goals

- Wisconsin Healthy Grown Potato Program, part 2/3, Requirements

- Wisconsin Healthy Grown Potato Program, part 3/3, Certification

- Pictures of Student Drawn Potato Systems

- Reflective Journal

- Prompt

- A key message in our course to date is the importance of how a system boundary is defined for gaining understanding of the system and how it works. For this week’s reflection please choose one of the systems we have discussed during class or you have previously considered in your journal. State the boundary of that system and how it was established or selected. Discuss how your view of that system might change if you change its physical, temporal or conceptual boundaries.

- Student Submission Examples:

- Student A

- Student B

- Student C

- Student D

- Student E

- Prompt

Week 5

Session 8-System Management I

Description:

- Began by briefly addressing student’s reflective assignments. Addressing the good quality so far, and encouraging students who had not yet submitted for this week to enter their assignment. They lose some points if it’s late, and many more if they don’t submit at all.

- The Cloud Institute Fish Game

- A resource management game with 3 fishing boats, and a stock of 20 fish that replenishes each round at a rate of 25% (rounding to whole numbers). We had the students play individually at first, then in groups.

- Comments from individual playing: Some were able to catch 18 fish, some depleted the pond. Some did experimental tactics at first to get a feel for things before pursuing an objective. Examples include alternating between 3 and 1, between 1 and 2, maintaining a rate of 2, etc. They observed the behavior of the other boats, and also considered ideal outcomes.

- We then formed them into groups of 4 and had them play again. Some comments from discussion were: If a group got below 10 fish, it wouldn’t recover very well. The actions taken depended on the goals of the groups. Their pursuit of maximum yield, versus sustained production, of individual yield versus group yield, etc., all had influences on how they chose to fish. We discussed the game’s goal of catching 18 fish, and how that was pursued. Students were also asked to generate some graphs reflecting their activity. Some graphed the number of fish they caught per round, some graphed the fish remaining after each round. No groups graphed the total number of fish caught.

- We asked if they came up with an answer to something. This was left vague on purpose, and tied in to our discussion of objectives and system boundaries. Some said they did determine specifics, others were more reticent.

- Lessons distilled by the group:

- Following the suit of a leading party can cause some troubles (ex. of India’s pursuit of coal energy on the basis that other countries had already taken advantage of the cheap fuel source)

- When you try to fish sustainably, you don’t end up with the most fish.

- Examples of common pool resources:

- fisheries

- aquifers

- grazing lands

- atmosphere

- Or, through the lens of systems analysis/systems thinking, almost everything is a common pool resource when examined on an extended time scale or through a wide view.

- Molly then spent some time discussing the work of Elinor Ostrom, on the governance of common pool resources, describing how she studied fishing villages along the Baja gulf in Mexico, and systematically catalogued mechanisms of governance and enforcement used around the world to sustain common pool resources.

- She raised questions of polycentric governance, and recognized the importance of the “rules of the game” dictating activities. Transparency was also a theme in her work. And, in addition to studying the tactics of governance, she studied how they arose and were carried out in community. Molly also raised the point of her collaborations with UW ecologist Steve Carpenter, who recognized non-linear dynamics in zooplankton populations.

- We ended class by introducing the mid-term group presentation assignment, and prefacing Thursday’s guest, Dr. Nurse Brook Anderson.

Materials:

- Readings:

- Meadows, Donella H. Thinking in Systems. (2008) Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, VT. Chapter 5

- Activity: The Fish Game

Session 9-System Management II (Guest visit from Dr. Brooke Anderson)

Description:

- Introduction by Molly – including the story of their introduction to one another and collaboration since.

- Brooke Highlights

- Systems thinker by nature – considered engineering but later pursued health care after realizing the body was such an amazing and complex system. Majored in nursing at UW-Madison.

- In 2001 joined the military, weeks before 9/11.

- Deployed in Northern Jordan in 2003, had to assemble a field hospital with limited staff and supplies packed in the 1990s, many of which had gotten moldy since. “sink or swim” training from earlier military years prepared her to take charge. This time got her comfortable with her nursing skills.

- Interestingly, the first deployment to Jordan resulted in less PTSD, even though the conditions were harder and supplies less prepared than later deployments – Brooke considers the closer emotional connections developed during the first, less prepared, stint as an important part of this.

- When she left the military at 26 she became a charge nurse and manager at a new “digital” hospital outside of Milwaukee. It was a mess in many respects and greatly needed the attention of a systems thinker, but leadership there weren’t prepared to take Brooke’s opinions, and the wedge in leadership there led Brooke to leave. She pursued a master’s degree in Education at UW-Madison, and worked as a pain specialist at the UW hospital following that training.

- Parable about her own health: The connective tissue condition causing her pain and difficulty, missed by various specialists, but eventually diagnosed by a patient who knew about the condition – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

- Now Brooke is at Medicaid as a consultant, helping to write and correct the rules and systems that distribute resources from that program.

- On the health system as a whole:

- Cost is remarkable and an important variable.

- Edwards Demming’s work in Japan to develop industrial organization practices: plan, do, check, act

- United States spends 1/10th of GDP on healthcare, and we struggle in many categories.

- What are the outcomes of all our knowledge and money?

- Why don’t we get better results more regularly?

- To Err is Human IOM report in 1999 – 44,000 to 98,000 yearly deaths from medical errors.

- Thinking at different levels:

- Person – focusing on the context of the individual at a specific time, the ripples of effects through their world and system

- Department – The story of the “passport” to increase hospital turnover time. Worked in some areas, but not in others, based on the differences between different parts of the hospital.

- Organizations – the story of the mattress pads: It was a success to remove the mattress pads from the linens bill in the hospital, but the expenditures on the official patient moving equipment that were picked up in a different department soared when the mattress covers were removed. The way the situation was divided lead to results that weren’t successful on a systems level.

- The Orphan Drug Act, focused on medicines that are only needed by a small number of people, rare genetic conditions. This situation led the FDA to change the rules for approval, and expedite these medicines more quickly. However, there are also stipulations that the medicines must be automatically approved, even if they are not that successful. On the “payer” level of healthcare this causes a huge problem, because the costs are often so high. A problem solved on one level is a problem created on another.

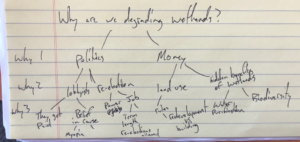

- Finally, Brooke introduced “the five whys” principle of investigating a system.

- We looked at the question: Why are we continually degrading wetlands?

- To do the exercise we came up with two potential first-tier influences: Money and politics

- then, for each first tier influence, we consider two second-tier influences: lobbyists/re-election, and land-use/hidden economic benefits of wetlands

- five times we do the same thing, interrogating each level of analysis by asking what two contributing factors might be. By the end, we have a large matrix that has taken us out of a linear view and into a systems view, just by repeating a brainstorm process. When considering intervention, Brooke asks which drivers repeat over and over across the system, and which second or third tier factors could be change to alter the behavior primarily in question.

- She also discussed the role of time in systems change: Many of these systems can’t possibly change in a single lifetime, but the efforts on a small scale do resonate. That, in part, is why Brooke loves to teach; the viral quality of the work means that change gets spread horizontally and vertically.

Photo of Liam’s notes from the “five whys” exercise:

Materials:

- Audio:

- Slides:

- Readings:

- Meadows, Donella H. Thinking in Systems. (2008) Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, VT. Chapter 6

- Reflective Journal

- Prompt

- When you played the fishing game you probably experienced one or more of the “traps” discussed in Meadows’ Ch. 5. Use your personal experience playing the game, your team’s experience, or some aspects of the class discussion to help you discuss the “traps” that the game reveals and their potential solutions. How do the traps and solutions change when you re-evaluate your fishing goals?

- Student Submission Examples:

- Student A

- Student B

- Student C

- Student D

- Student E

- Prompt

Week 6

Session 10-Systems and adaptation (Debrief of visit w/ Dr. Anderson)

Description:

- Began with some notes on class format

- Brief connection between Panarchy and Brooke. Panarchy as a model of change in complex systems, Brooke as an intervenor and actor in complex health systems.

- Reflection on the journals: Is everyone enjoying the process? The prompt is merely a springboard, not a straitjacket – they should all feel free to diverge when they need to or have something else important they would like to say. If, for example, they’d like to return to a discussion of boundaries on a certain topic, they should feel free to do so.

- Note from Molly on the form of class: We have spent time defining the essential definitions of systems (Meadows, etc.) and now we are working on multiple layers. We develop the vocabulary, then use it to apply systems thinking across different levels of analysis.

- Main activity: Reflection on Brooke and her talk

- First, we defined health:

- Something is healthy when it is in order and as it should be, versus out of order or awry in some way. Health of systems often involves self-maintenance or resilience.

- Health taught to kids through video games: The health meter on an object shows how much damage it can tolerate. It is a quality to be preserved and monitored.

- Health applies to relationships, ecosystems, healthcare.

- The word health itself is an old Germanic root relating to “hale” or whole

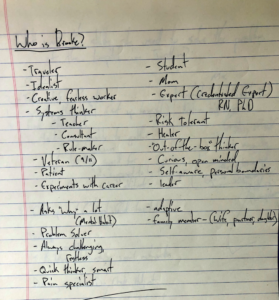

- Then we asked: Who is Brooke?

- Discussion continued regarding some of her stories.

- What were the skills she used to solve the problem of the hospital in Jordan? What did she do?

- Determined her goal

- Took stock of options

- Found alternatives because the supplies were moldy

- Gather resources in any means she could, spent little time mourning the fact that things weren’t “how they were supposed to be.” She brought the “sink or swim” attitude the military had taught her.

- She ended up creating a functional field hospital.

- Brooke talked somewhat about the Deming model – Plan, Do, Check, Adjust

- We described the Menominee Tribe forest management techniques of system maintenance and intervention – it’s their home and livelihood.

- First, we defined health:

-

- The Mattress Pads Parable

- Describes the perils of not thinking in systems

- The way the budget was divided meant one area was incentivized to push costs off to another, even though they were both working for the hospital, with what should have been similar overall goals.

- Without the mattress pads, there were: more injuries to nursing staff and more torn sheets, along with the higher expenses now paid to transport patients without the mattress pads.

- Lessons:

- Systems thinkers often depend on “narrative” data. Stories, anecdotes, etc.

- (Molly: Yet there remains a bias toward data that is quantitative. Often we find a narrative and backfill in the data later on.)

- Always consider unintended consequences of systems intervention.

- Describes the perils of not thinking in systems

- Other thoughts from the class:

- The rigidity of Brooke’s new workplace: No personal conversations at work.

- Unintended consequences of lower morale, and a lack of the important peer-to-peer connections that enable collaboration and innovation.

- Brooke said she was labeled “obstructionist” in the Wausau hospital for advocating against the new heart surgery unit. Doing the right thing is not always appreciated. As Molly said, often the system has its own inertia that is difficult to disrupt.

- Our modern medical system: Built to cure disease originally, slowly transitioning to managing health.

- In many cases of systems change, in health and elsewhere, we overvalue the glitzy “leaders” in institutions and undervalue the people who are on the ground doing the work every day.

- Naming a system element: When the 1999 study came out on preventable deaths in medicine there were huge effects across the health system. A problem had been named, which allows us to see the problem, and forces us to manage it.

- Brooke’s Connective Tissue Disorder

- Frequently dislocated hips, shoulders. Was in serious pain, and saw many specialists. Other symptoms included her high level of flexibility, her ribs pop when sneezing, her uterus fell out, she was clumsy, and she often tore ligaments.

- In coordination with her work on the opioid safe-prescribing task force she met a patient being treated for drug-addiction, who, in that relationship was empowered to ask Brooke about her condition. The patient was actually able to make a successful diagnosis of the issue, which was actually a genetic condition effecting connective tissues (how systemic!)

- In this case and in others, we learned how narratives set boundaries. Because Brooke was working on the task force, she had a more collegial relationship to the patient than is typical in medicine, especially for patients of addiction. In this context, and in that social story Brooke and the patient established a relationship that allowed a conversation and diagnosis.

- The Mattress Pads Parable

Materials:

- Readings:

- Gunderson, Lance H., and C. S. Holling, Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. (2002) Island Press, Washington, DC. 1 – “In Quest of a Theory of Adaptive Change”

Session 11-Resilience and Adaptive Cycles

Description:

- The chapter from Panarchy was one of the more difficult readings of the semester so far, so we devoted most of lecture to understanding the model and its implications for thinking about change.

- Rob began with an exercise asking students to describe “Health” in a non-human environment. The point of the exercise was that it’s hard to characterize such a quality when humans aren’t ascribing value to the ecosystem.

- Some things they came up with were:

- Biodiversity, resiliency, functions (desirable), absence of “bad” disruptions, presence of “good” disruptions, energy in should approximately equal energy out (it should be accumulated or balanced), the system should be adaptable (Darwinian evolution of sorts), it also needs to contain the right balance of chemicals and temperature and water to support life in the first place.

- In the discussion came up the fact that “health” depends on what you want, and, in a non-human environment it is hard for humans to determine what should be valued.

- This was an appropriate segue into what Rob was after: How do we know what an ecosystem should look like and how it should be in a “natural” state?

- In Panarchy, chp. 1, the authors develop “myths of nature” such as “nature flat,” “nature balanced,” “nature resilient,” and “nature anarchic.” Each of these myths describes a common attitude humans possess about how nature operates, and each is flawed in some fashion. The authors go on to develop a more dynamic understanding of nature, that incorporates elements of the “nature resilient” model, as well as a more apt “nature evolving” model.

- The combination of those two models brings us to the panarchy diagram in chapter 2, that attempts to model transformations in human and natural systems.

- The model has a number of different phases that characterize stages of a complex system’s evolution. It took some explanation and examples from Rob to get the students to grasp each different element, but they eventually understood the model for the most part, with some confusion remaining about the “connectedness” and “potential” phases.

- Toward the end of class, students were broken into groups to continue their discussion of the Panarchy model and apply it to a system they were familiar with. They came up with some good examples, one being a student cycling through semesters of college, another being a water cycle, etc.

- The groups served a dual purpose because they were the groups the students would remain in for their midterm project. At the beginning of class, students filled out a small slip of paper listing various skills useful in group projects: Research, Visual/artistic ability, Writing, Coordination/Organization. Students put 2 stars next to their strongest attribute, and 1 star next to their second strongest. They also listed their names on the paper. During the lecture, the slips were collected and sorted so that each group of 4 students had at least one person identifying themselves strong or very strong in each skill category. The groups were loosely balanced for gender diversity as well, trying to avoid all male or all female groups (perhaps that is not necessary, but it seemed customary to mix groups).

- Molly made a comment at the end of lecture about the Panarchy model as a key to systems intervention, as it tries to detail when a useful time to change a system would be. She brought up the fact that ecologists often feel as though they’ve achieved something when they’ve described a system, but that is not true. Description is not an intervention, but it can facilitate an effective intervention. The Panarchy model might be particularly useful in that sense, as we get students to think more and more about potential systems interventions and how to execute them.

Materials:

- Supporting Doc:

- Readings:

- Gunderson, Lance H., and C. S. Holling, Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. (2002) Island Press, Washington, DC. 2 – “Resilience and Adaptive Cycles”

- Reflective Journal

- Prompt

- Brooke Anderson shared several of her experiences as a systems thinker and systems actor in health care. Use an insight or lesson from one of Brooke’s stories to explain or describe a story about systems in your own life.

- Student Submission Examples:

- Student A

- Student B

- Student C

- Student D

- Student E

- Prompt

Week 7

Session 12-Institutions and Systems

Description:

- Molly lectured primarily, with input from Rob on occasion.

- The lecture in 3 parts:

- Fallujah, Juarez, Baltimore.

- General thoughts on the podcast from the class:

- (For context: it’s about surveillance planes that take high-resolution photos every second, enabling the owners of the data to track activity of cars and people through time. The resolution is not high enough to make out personal or vehicle identification, so it is most useful to trace movement from before or after a specific crime took place.)

- -The limits of the image resolution are important, and that’s a choice made by Ross McNutt.

- – One student comments that satellites may already be doing these things, so perhaps this technology isn’t that different from things that are already going on.

- -Another student talks about the importance of the free press. This story is from 2015, so maybe things have developed. If they have, why haven’t we heard about it? Perhaps there isn’t enough bandwidth for the public to consider every issue thoroughly.

- Molly on a core issue of this podcast:

- Methodologies create knowledge. Knowledge from new methodologies (like this technology) lack clear and enforced governance. That creates a lot of chaos and uncertainty on the “edge” where these new technologies enter.

- Rob:

- Systems thinking is about revealing previously invisible relationships. In this case, the relationships were revealed through technology, and the use of that new knowledge was concerning.

- Part 1: Fallujah

- Roadside bombing in Iraq were a huge problem during the US war effort, and no department succeeded in minimizing the damage. IED casualty rates were very, very high. The story is personal for Molly, because her journalist cousin, Bob Woodruff, was struck by an IED. He survived, but was injured.

- The military branches did an experiment on IEDs. Some 60km roadways were left unattended and unprotected. The branches did nothing to prevent the bombings. On other stretches, they pulled out all the stops, doing everything they could to prevent IED attacks. At the end of the 3 month trial period, they found no significant difference in IED deaths between the fully protected and the unprotected roadways. This signaled that their efforts had been fruitless—they would need a new way to approach the problem. Many of their fundamental assumptions about how to prevent IED attacks were off. Luckily, during that time, the persistent surveillance planes were flying above the city tracking the activity on the roadways. This enabled a new approach. They studied the activity that happened around a bomb site prior to an explosion, and were able to uncover the tactics used by bombers. By tracing them back through time using the visual images, the US troops were able to find the base camps of the roadside bombers and take out the people who were responsible for the serial roadside killings.

- This technique of PSS emphasizes some systems methods: It captures everything that we might care about, instead of only capturing the things we know we care about in advance. This allows better inference. Looking at broad-scale data across time is important in systems science. Enables the discovery of formerly unknown unknowns.

- Part 2: Juarez

- South of El Paso, TX in very northern Mexico. Very violent city, filled with activity from gangs who traffic people and drugs across the border. Essentially a war zone. No one’s life isn’t effected by the violence, and regular citizens die regularly. Often, young men have no choice but to enter gangs.

- The Arnold Foundation of Texas sponsored PSS in Juarez. They focus on work around transparency. Which, Molly says, is an essential concept in systems science, though it hasn’t been formally studied much. Transparency really changes the way power is wielded, and who wields it.

- The planes captured a drive-by shooting. Multiple gang-related cars cornered the vehicle of a female police officer and shot her in her car. Because of PSS, the police were able to trace the vehicle involved back to a primary basecamp. After monitoring that activity further back in time, authorities were able to see that this house had been responsible for more than 1500 killings in a similar method. Tracing them back to their camp wouldn’t have been possible without the technology. One question from the class was this: Who did the policing in Juarez? Mexican authorities, or the United States?

- Aside on national security and intelligence principles:

- Activity-Based Intelligence (ABI) is a popular new systems technique toward intelligence.

- Radio interception, developed in WWII, is about intercepting the signals of enemies and interpreting the messages. This is now called Signal Intelligence, or SIGINT

- Geographic Intelligence has to do with physical whereabouts of all kind. Resources, people, interactions, activity areas, etc. Called GEOINT

- Human Intelligence is more traditional spy work, usually by “double agents” who are aware of both sides of the system. They discern trends not accessible through other means. Called HUMINT.

- Taken together, SIGINT, GEOINT, and HUMINT enable a kind of intelligence thinking called “patterns of life” where we might be able to discern patterns occurring over time and better prepare in advance.

- Intelligence Director James Clapper has said “Everyone’s gotta be somewhere”

- Hagerstrand is a mathematician using similar principles – we should be about to find patterns for all behaviors, and understand them mathematically.

- 1st Law of Geography: Everything needs to be somewhere, and we should be able to find it.

- Part 3: Baltimore

- Arnold foundation funds PSS in Baltimore, a city rife with crime, where many citizens have an incredibly untrusting relationship to the police.

- The PSS planes fly a customary civil flight plan, circling around the city.

- It went largely undetected and didn’t bother most people for a while. Then Freddie Gray, a 25 year-old disable black man, was arrested by the police with unnecessary force, and fell into a coma while being transported by police. He later died in a trauma center of injuries to the spinal cord. The officer driving the van was charged with second-degree murder.

- This event set off large protests over police brutality toward black communities, and especially toward black men. This sharp incident occurring in a city that already had police tensions inspired even greater distrust. Naturally, citizens were not comfortable with an unaccountable police department controlling this kind of pervasive surveillance data. Tensions were exacerbated.

- Broke into small groups. Asked what boundaries were imposed in the Baltimore example, and what boundaries might need to be imposed in other cases.

- Thoughts from groups:

- We are already tracked by iPhones and satellites, so perhaps this technology isn’t as new as it seems.

- Private companies could control the data in a gov. contracting capacity. If that’s the case, who might they sell the data to?

- Perhaps a system could be put in place where data is only accessible to investigate certain kinds of crimes.

- Perhaps the data is publicly controlled, but powers are separated. One group controls primarily and another can request for appropriate matters, detailed by some policy.

- A private company, regulated by the government could hold the data. That might enable higher levels of safety, as well as higher ethical standards, depending on the codes of the business.

- Thoughts from groups:

- In closing, Molly points out some nuances of systems science:

- There is a distinct difference between describing a system to understand it, and describing a system to intervene in it toward a desired outcome.

- Also, many times with systems-scan methodology across time, we see an effect without yet knowing what causes it.

Materials:

- Audio: Podcast on persistent surveillance systems – Systems and social limits.

Session 13-Team Time

Description:

- Students were asked to spend some time considering potential topics for the midterm assignment.

- Brief introduction from Rob on the project, remainder of time spent in groups of 4, working toward mid-term.

Materials:

- Activity: Work with your team to start to put together your mid-term presentation

- Reflective Journal

- Prompt

- Effective system thinking methodologies can reveal previously invisible relationships. How should we govern these methodologies? What should be revealed? What should remain invisible? How should information get used? Who gets to use it? Who should decide? Using the specific case of persistent surveillance in Baltimore that was discussed in class, take a stand for or against the use of this methodology, and describe how you think it should be governed. Defend your opinion in your reflective journal this week. If you have doubts make sure you discuss them but try to come to a clear, well argued conclusion.

- Student Submission Examples:

- Student A

- Student B

- Student C

- Student D

- Student E

- Prompt

Week 8

Session 14-Identity and Systems

Description:

- Before-class activity: Explore We Become What We Behold

- “We become what we behold. We shape our tools then our tools shape us.” – Marshall McLuhan

- Reflections on the before-class game:

- Timing really matters. The intrigue of the system, and the feedback response guides us toward violence as we document the system.

- Mass media allows incidents to become stereotypes, reflecting subtle in-group and out-group biases. Usually dormant, but easily triggered in crisis.

- No controlling feedback loop in the system.

- Reflections on the Racialization Workshop:

- Differences are learned and reinforced.

- We are all embedded in racialized systems

- The effects cascade in many ways.

- Heterogeneity in a system

- When that quality matters, when it doesn’t.

- False perceptions of “objectivity” in our media—actually embedded in a value-laden paradigm

- ABC news now showing intentionally happy stories to mitigate social effects of negativity in media.

- Privilege allows us not to see the racialization system unless we look for it.

- The importance of using a “we” dialogue instead of a bifurcated “us” vs. “them” dialogue.

- Where do the problems reside within us?

- Rob: in the 1930s, depression era home-loan policies quantified high-risk and low-risk areas. Essentially the feds authorized racially-biased loaning per the desires of the culturally dominant white majority.

- At first the Italians were not considered white. Eventually they were folded into the group of “whites.” For what reasons may this have occurred?

- In-class game on segregation in housing: Parable of the Polygons

- Simple rules govern complex behaviorsIn our culture we often value stability, and we adhere to certain moral values, even in playing online games.

- In Milwaukee and other places, the prevalence of lead was particularly high in red-lined neighborhoods, with ongoing health effects to learning and development. (Freddie Gray was disabled by a lead-poisoned boyhood home).

- The problems that we can see, and the problems we can’t.

Materials:

- Slides

- Supporting Doc:

- Activity:

- We Become What We Behold

- Parable of the Polygons

- Readings:

- Powell, John A., Connie Cagampang Heller, Fayza Bundalli, Systems Thinking and Race: Workshop Summary. (2011) The California Endowment.

Session 15-Sustainable Systems (Visit from Dr. Paul Robbins, Director of the Nelson Institute)

Description:

- Paul’s Presentation on Systems Research in India

- 20 min west of Bangalore by plane – biodiversity hotspot with lots of endemic species

- heavily farmed – Coffee, Tea, Areca Nut, Rubber

- In such a manmade place, what maintains the biodiversity?

- It’s very rainy ~250 cm of rain each year, the mountains are the barrier of the drier east and the wetter west.

- How do these farmers accidentally reproduce biodiversity?

- Surveyed 65 areca farms, 61 rubber farms, 61 coffee.

- Birds and frogs were used as ecosystem indicators, both were primarily counted by ear

- Coffee had a high level of biodiversity – Why? It’s shade grown, so it must be under a maintained canopy, AND farmers can sell timber when coffee prices get too low.

- The surveys found that avian diversity correlated highly with tree species diversity.

- Silver oak was a common monoculture tree, imported by the British and without much support for biodiversity.

- It’s hard for farmers to keep such tree diversity, requires lots of labor, but is better for growing Arabica (superior coffee to Robusto)

- No correlation with tree diversity and farmer education.

- Shade grown coffee requires a rich canopy – but when prices are low for Arabica, it’s best to switch to Robusta so that canopy doesn’t need to be maintained.

- In cases where farmers had monocultures and wanted to simplify the landscape it was often because they felt “the workers were lazy”

- they wanted better wages, better living conditions, more frequent breaks, etc.

- Why? Cultural aspirations, and labor scarcity—not enough people, so more is required of employers to attract workers. The population in S. India is flatlining or declining, below replacement birthrate.

- So… birds and frogs come from cheap labor which enables the production of diverse tree canopies.

- aside on population:

- flat world population by 2050 (less than 2.1 birthrate), peak growth rate was in 1965.

- Why do people have fewer kids now?

- Kids have gotten more expensive

- We used to make more things at home, now we tend to purchase everything

- No need for having children to work on family farm

- Women who work have higher opportunity cost of children.

- Better women’s health care and contraception

- VERY high correlation with women’s education and birth rate decline.

- Robbins suggests a large issue of “global baby bust” in ~25 years.

- Paul’s personal story:

- Studied anthropology and archaeology at UW Madison in the 80s, followed a professor to India to do work after undergraduate, and loved being in India (didn’t like archaeology as much) and wanted to study systems of grazing and environment there (complex systems, though he wouldn’t have called them such at the time)

- For example, the invasive quality of the mesquite tree from the SW United States all across India.

- Studied the use of protected lands as grazing areas, asked what systems produced, how they changed with the influence of people.

- India is the future, because every aspect of the country has been humanized: we are influencing the Earth’s systems everywhere we go, there is no such thing as untouched “wilderness” anymore

- Now, at the Nelson institute:

- Channels his previous work leading big teams of really different people – like “herding cats” hard to organize everyone to work together in a common vision. Everyone is doing applied work in some way or another.

- Likes the work as a director because he can “fix things under the hood” and remove snarls in other people’s research. How did he arrive there? Some kind of path dependency, where things in the system are moving in a direction that is unpredictable but reinforcing in some ways.

- General life rules and lessons:

- Pick up the phone – he called the graduate school that hadn’t accepted him with funding and asked why that was. When he called he found they had an extra spot, and he began studying there 2 days afterward.

- Gather as many skills as you can – it’s the skill that’s not your primary skill that will make the difference.

- WI and UW:

- WI population is level or shrinking, especially in rural areas and N. Wisconsin.

- 50% of students graduating from UW don’t have any debt.

- The world is a heavily human influenced place, and we must do a good job operating within it.

Materials:

- Audio:

- Readings:

- Slides

- Reflective Journal

- Prompt

- Discuss the connections (or disconnections) between our class on persistent surveillance systems (Oct. 16) and our class on systems thinking, identity, and race (Oct. 23). Describe whether and how your understanding of either topic has changed. Refer to the readings, lectures, and in-class activities to deepen your reflection.

- Student Submission Examples:

- Student A

- Student C

- Student D

- Student E

- Prompt

Week 9

Session 16-Sustainable Systems II (Debrief of visit with Dr. Robbins)

Description:

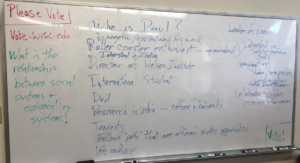

- Paul Robbins recap (recorded during class)

- Who is Paul?

- roller coaster enthusiast

- energetic

- director nelson inst.

- former international student

- Dad

- Researched in India

- Enjoys going on tangents

- Follows paths, makes own opportunities

- gives life advice

- leader of change

- Researched

- Birds, frogs, labor, wages, fertility rates, farming practices

- Linked them all together to tell a story about human and natural systems

- Loves India – claims it’s the future -humans and nature interacting for thousands of years

- PhD in Geography (Political Ecology) from Clark University in MA

- What would we learn from Paul to study biodiversity in Northern Wisconsin?

- -We should talk to people

- -consider changes to the land over time

- -ask how people use the land

- -look at how human demographics are changing

- -Consider the agricultural systems in the region

- -Consider existing governance and legislative techniques

- Students broke into groups to consider:

- What is the relationship between social systems and ecological systems?

- Some groups felt that there was a divide between the two systems, especially in developed countries. Other groups had a more inter-related view, where social systems and ecological systems depend on one another to exist and evolve. Based on Paul’s research, groups challenged the convention that humans are “bad” for ecosystems.

Materials:

- Readings:

- Gunderson, Lance H., and C. S. Holling, Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. (2002) Island Press, Washington, DC. 4 – “Why systems of people and nature are not just social and ecological systems”

- Audio

Session 17-Welcome to the Anthropocene

Description:

- Students were asked to spend time exploring the Yahara 2070 website developed by the UW department of limnology.

- In class, we did an extended brainstorm on the models and narratives. Liam was helping to direct the discussion and write on the whiteboards, so documentation is limited.

- The discussion covered the four different scenarios that were presented in the simulation, considering the positive and negative consequences of each different approach.

- We asked what similarities were between the four scenarios, and we also considered how they differed. We asked who would decide, and what we can do.

- People generally preferred the connected communities idea to the others, though some were intrigued by the high tech alternatives.

- Each scenario brought about different ecosystem conditions, and documented a different potential social response to each option.

- There are social and environmental systems galore that need to be considered in this model, and we made some effort to emphasize the fact that it is not really a distant hypothetical, but a potential reality that might arise in our own lifetimes (particularly for most of the students, who are around 21 years of age.)

- The discussion was scattered at times, but generally explored the complex systems surrounding the development of human and environmental systems in the face of climate change.

Materials:

- Readings:

- ExploreYahara 2070, scenarios depicting the future of the Yahara watershed under different courses of action. https://wsc.limnology.wisc.edu/yahara2070

- Reflective Journal

- Prompt

- Using insights from Paul Robbin’s presentation and from this week’s discussions, course readings, and assigned websites, reflect on the following questions: What is the relationship between ecological systems and social systems? What aspects of these systems are important to consider if you want to intervene in them?

- Student Submission Examples:

- Student A

- Student C

- Student D

- Student E

- Prompt

Week 10

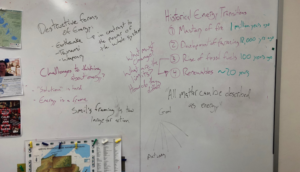

Session 18-Wicked Problems I – Energy and sustainability

Description:

- Begin with discussion of Wicked Problems: What are they?

- Complex

- Insidious

- Time-consuming

- Include negative feedback loops

- Double Bind Elements

- Require a systems framework

- How do these feed into energy systems?

- Investments require complicated cost-benefit decisions ‑ social, physical, environmental factors

- Everything is connected in and to energy systems

- Energy systems change over time

- Who is Vaclav Smil?

- Czechoslovakian

- Grew up in Soviet Repupblic

- Moved to the US in the late ‘60s, then to Canada

- Pessimist/Realist

- Individualist as a scholar and in views on energy systems change

- Prolific author on energy

- Chopped wood as a young person

- Talked more specifically about chapter 2—students did not offer much in discussion, so we broke into groups, where they attempted to develop 3 or 4 implications from the descriptions of energy systems Smil offered.

- We asked them to: Come up with 3 or 5 relationships from this chapter that you think are important for future human energy policy. Explain why. (Hint: focus on connections with other systems—social, environmental, economic)

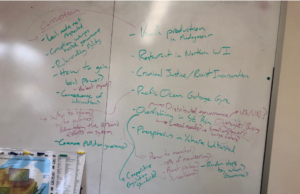

- Those findings and discussions from the remainder of our class were best documented on the whiteboard, photos below.

Materials:

- Readings:

- Voosen, Paul, “Meet Vaclav Smil, the man who has quietly shaped how the world thinks about energy.” Science. March 21, 2018 (http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/03/meet-vaclav-smil-man-who-has-quietly-shaped-how-world-thinks-about-energy (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site.)

- Smil, Vaclav, Energy – 2ndEdition. (2017) Oneworld Publications, London. (Ch. 2)

- Supporting Doc

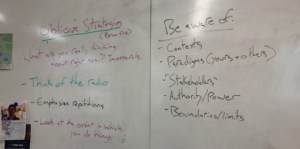

Session 19-Wicked Problems II – Energy and sustainability

Description:

- Begin with a few slides from Rob. Still on theme of wicked problems, though this time with regard to Smil’s chapter describing energy use over the last centuries.

- What were students surprised by?

- What was notable?

- Brief discussions with class on those topics. See photo below.

- After the discussion with the entire class, we broke into discussions within each student’s midterm project group. We asked them, per Rob’s slides, to map the current energy system of the world. Where does the energy come from, who uses it, how does it work, etc. It’s a big system to map, and we told them it would be a challenge, but it was a good exercise.

- They worked primarily with pencil and paper to draw the systems maps, and also conversed and made lists, etc.

- There wasn’t time in class to share out, but the discussions were energetic as they attempted to find a starting point and follow the systems thread out from there. Below are some messages we included to prompt their thinking.

- (Oblique Strategies is a thinking-tool card deck from musician Brian Eno, available online here: https://www.joshharrison.net/oblique-strategies/)

Materials:

- Slides

- Readings:

- Smil, Vaclav, Energy – 2ndEdition. (2017) Oneworld Publications, London. (Ch. 4)

- Reflective Journal

- Prompt

- There is no journal assignment for this week. Be ready for a challenging topic next week!

- Prompt

Week 11

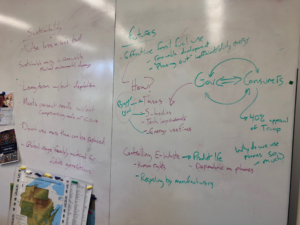

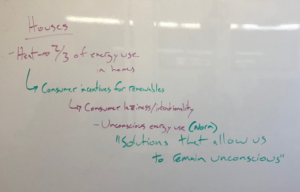

Session 20-Wicked Problems III – Energy and sustainability

Description:

- Began class with framing from Rob. Discussing the chapter from Smil on energy use trends in daily life, and asking what surprises students encountered.

- We then broke into group work to describe how we might transition from our current energy system into a more sustainable energy future. We asked what energy sustainability means, and how we might get there.

- The responses were captured on the whiteboards, with photos below.

Materials:

- Readings:

- Smil, Vaclav, Energy – 2ndEdition. (2017) Oneworld Publications, London. (Ch. 5, 6)

- Higgins, Adrian. “High-tech farmers are using LED lights in ways that seem to border on science fiction.” Washington Post. (2018). https://www.washingtonpost.com/classic-apps/the-cutting-edge-tech-that-will-change-how-we-feed-ourselves/2018/11/06/775ac684-ce66-11e8-a360-85875bac0b1f_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.a474dc192b72

Session 21–Warm Data with Nora Bateson

Description:

- Nora Skype call and conversation with class

- Club of Rome anecdote: All the big scientists are stuck in their silos of thinking, and only certain perspectives were allowed to breathe in their scientific community (Johann Rockstrom, Potsdam Institute)

- The Club of Rome has been describing the limits of growth for 50 years—makes you wonder if they aren’t saying it right.

- The tone, mood and aesthetic of their lectures was lacking in certain things, and prevented Nora from raising many important issues:

- They had no mention of the family, of mental health, or health whatsoever, no recognition that “in the midst of climate change, there will be culture change”

- The separation of our lives into externalized systems diagrams is not serving us well. What is it about that place and that form that prevents things from being said?

- Every organism has, at some point, to change the way it’s surviving in relation to its context.

- The survival of any organism has to do with its perception of its context. Hence, we must perceive our world in a new way.

- Recognizing the complexity inside ourselves lets us notice complexity on the outside.

- Nora has been steeped in this her entire life, helping with her father as a child. Not because she’s a rockstar, but because kids have a much easier time seeing wholes than grown-ups, who have learned to do otherwise.

- The world she saw as a kid was a world of interdependencies, in their home they called out reductionism whenever they saw it. Breakfast was never just breakfast, but a sea of interdependencies.

- Systems thinking was life. Period.

- She came to that view from the inside.

- As her father said, you don’t really get it “until it comes in to your elbows.”

- And in that view, systems thinking isn’t just an external conceptual framework, it’s about the way you see yourself in every aspect of your life.

- Transcontextuality (from Steps to an Ecology of Mind): Where living things always exist in multiple contexts.

- Complex systems almost never exist solely in a single context. They exist at once, like us, in dozens of contexts. Each aspect informs the others.

- In us, there is the system of our microbiome, and the system of our social relationships, and each of those contexts does inform the other.

- Considering ourselves in all of these contexts at once, we see that we exist as a council: Like the native American elders, we hold commune with our multiple selves to find inner consensus or dissonance across our many contexts.

- Essentially, it takes complexity to perceive complexity: When we see ourselves as complex, we can see other people and systems that way.

- Using only the academic models of complexity, one will certainly miss things.

- “The more you use your sea-anemone tentacles of multiple-contexts, the more you perceive.”

- To do this, we must dive into inner realms that are emotional, artistic, poetic, irrational, calculated, paradoxical, etc. All these realms hold council within us and inform all insights.

- Q: If it takes complexity to perceive complexity, how do we get it in the first place?

- A: Well, it’s there from the get-go. The real mystery might be how we ever manage to get un-complex. In a sense it’s a western cultural tendency: Happiness in the west is monochrome, but in fact happiness and joy depend on other relationships to shape their context.

- Q: What about situations where we intentionally separate ourselves, intentionally code-switching between groups and with people? How is that still informed by our whole self?

- A: The other parts are never gone, they are just speaking less loudly at those times. In both the Zombie and the Hitchhiker stories, there was spontaneous use of this wide-angle view of the complex situation. The scripts and codes of those moments were subverted by a sudden view of the bigger picture—such insights show how the whole parts of ourselves are operating in the background, even if one aspect is being presented most.

- People always talk about the positive connotations of emergence, and we don’t like to remember that “emergence” is a part of “emergency.” And it’s in these moments when we need to see complexity most (police shootings come to mind.)

- Q: How do we introduce complexity into the rigid and reductive tendencies of institutions/bureaucracies, whose goal it is to turn complex problems into tractable, linear issues?

- A: Thinking of something like health, we realize how transcontextual it is: Family, diet, exercise, culture, education, laws, policy, housing, partnerships, sexuality. These are all contexts of health, and it becomes quickly unclear which institution is supposed to be mitigating an individual’s health. Probably it doesn’t exist in any institution, they exist in the relationships between them.

- If the question is “where should you poke if you want to influence health,” then I would suggest operating in the liminal space between institutions. Institutions, in this sense, are just the points through which contexts cross, with vast areas between them.

- For another example, if we want to improve educations, where should we put the improvement:

- Schools, Jobs/careers, parents, natural environments?

- In our democracy, politicians have a certain duty of care for the safety and security of the citizens, but we’ve known of climate change and limits to growth for 50 years, and nothing has changed. Why is it moving so slowly?

- There are lots of limits to policy action, and systems action needs to be as complex as systems change itself.

- There are great opportunities for change that bubble up out of the minutia if we are aware (like the zombie story). But we don’t see these opportunities if we’re looking directly at the problem we’re trying to solve.

- Donella Meadows calls these “leverage points,” but that is too mechanistic. “Entry points” might be a better term.

- The way we continue to burn fossil fuels is not logical, so the way we stop may not be either.

- We have deferred to linear institutions to mitigate non-linear problems.

- Q: What is warm data? How can you define it?

- Warm data is warm because it’s in the company of its contexts. Research since the 1600s has been about pulling things out of their contexts, to make observations repeatable et cetera.

- But complex systems are given their complexity due to their relationships. If you pull something out to look at it, you lose its relationships. Complexity can be slow like a forest, or fast like an election campaign. In either case, warm data is about observing a system in its multiple contexts to see the complexity.

- “Most problems in our world are the result of previous solutions.” “Previous solutions that weren’t considered with enough complexity.”

- Like the pesticide RoundUp, for example. It kills the enzyme/protein relationship in small invertabrates, and wasn’t supposed to harm humans, but it is, in fact, harmful to the trillions of bacteria that we rely on, both in our bodies and in the soil.

- Food is made of relationships—the warm data in that context is the relational work throughout the entire system.

- Nora thanked us for letting her walk us through the wide misty forest of systems thinking beyond the diagrams and discussions of feedback loops.